While the Shenandoah Valley is first in my heart among favorite places, Georgia holds a very special place in it as well… specifically, coastal Georgia. That’s where my mind seemed to wonder off this past weekend, as temps here in the Valley teetered between the upper 50s/lower 60s. That’s weather reminiscent of winters in coastal Georgia. Yet, being unable to hop on a jet, and head to Savannah, Brunswick, Jekyll Island, or St. Marys, I figured I’d tinker a bit in the Southern Unionists claims for one of the coastal counties.

Since Savannah was the first place that came to mind, I chose Chatham County as a point for exploration. That said, however, my search in Chatham’s record of claims lead me to an incident which actually took place in nearby McIntosh County.

Now, looking at Southern Unionist claims for coastal Georgia is most certainly unfamiliar territory to me. Not only are these claims typically different from those I find in the Shenandoah Valley, the majority of those which were approved came from either free blacks or freed (and, yes, that freedom was tied to Sherman’s arrival) slaves. I moved through a few before I came upon one that particularly struck my interest. It also happens to mesh well with something that stands in modern “memory” of the Civil War… the part of the movie Glory in which Darien, Georgia is burned.

What is interesting is how the burning is portrayed in the movie, and then how it is described in the claim. If you have the movie Glory handy, I highly recommend looking at the segment that deals with the burning of Darien. After watching the segment, go through the claim and consider how various points in the claim stand in contrast to the portrayals in the move.

Enter the story of Elizabeth Geary… not from the movie, but from the claim. I’ll let her and her two sons do most of the talking…

A native of Georgia, and born in Darien, at the time of her application to the Claims Commission, she was a seamstress. She was also a mother of six, and a widow, her husband having died in February, 1871.

While at Darien I lived on my own property. I owned my own house and lot. The title of the property was in the name of my first child Mary Francis Geary this was done and comply with the statutes of Georgia.

I was always free, of a mixed parentage, a white father and a colored mother. My husband was the same. I was regularly married according to the laws of the church, and also received a license from McIntosh County contrary to the usage of the state. I have always lived so far as a colored person could, in good circumstances.

According to the details of the claim, the family’s property was worth note… a home, a grocery store… and very well-furnished.

Elizabeth’s son, William Geary, recalled of the dwelling:

I think it was about 30 by 40 on the ground, a story and a half high. It was plastered and painted outside. There were two small out buildings besides the dwelling and the kitchen. The house was shingled with short cypress shingles and weatherboarded with pine.

There was furniture in the dwelling. The parlor was furnished with mahogany furniture; don’t know the size of the parlor. It was carpeted. There were eight mahogany chairs besides a rocker finished with hair cloth. Two tables in the parlor, one a marbletop, the other was a large mahogany dining table. There were four flour [sic] pots and two vases on the mantle, also a mahogany sideboard. A… mahogany stand in the room. Brass finder and fire dogs at the fire place and large mirror with mahogany frame, one large picture over the mantle, do not remember what it was, exactly, it was a religious scene.

The dining room was furnished with a table, stove (not a cook stove) chairs ,and sofa, then were three bedrooms, mothers’ room was furnished better than the rest. They were all furnished appropriately.

Elizabeth seemed to put more emphasis on the kitchen:

…kitchen furniture & crockery… pots, kettles, ovens & crockery, tubs etc. Everything complete. These things were not old, all in good condition. I bought them while the rich folks were selling out run away from the war. So it was good stock. I don’t think $200 would replace the things but I have no good idea what it would cost.

Part of the reason behind the well-furnished home was Elizabeth’s father who “was… a man of property. He left a support for me in his will; from this I was able to have things nice.” Yet, apparently because of the “color-barrier”, even after the war, the executors of her my father’s estate had not given Elizabeth her “rights”; “the property is in litigation now. We are trying to recover our share of the property.”

Elizabeth’s husband also “had a good deal of property”, and like Elizabeth “could read and write.”

With the coming of the war, the Geary family remained devout Unionists. Elizabeth remarked,

I always said my desire was that the South should be conquered. The colored people were not allowed to say anything, but I would say this at the risk of my head. My sympathies were always the same before and after the passage of the Secession ordinance. Being a woman and colored, of course, I had no vote.

William Geary also remembered the risks of being outspoken on the matter:

The colored people were as a general thing, all union people; there were few exceptions. These exceptions [were] more from ignorance of the few being so taught to think. They were told the Yankees would send them to Cuba and sell them, or that they would be put in the front of the army and be killed off. I was told these things a hundred times but never believed them. The reputation of my father and mother was that of union people among the colored people. I don’t know how it was among the whites. It was not safe to express an opinion favorable to the Union cause among the white people.

For their Unionist sentiments, the family was under a watchful eye. Elizabeth remembered,

I was threatened with death and injury to my person, family,m and property on account of my Union sentiments, and so was my husband. They threatened to hang me for telling the union soldiers that the Rebels were near. I had some friends, who had known me from childhood, in the camp, and they kept me advised and discouraged them from carrying out their threats. This was before the burning of the town of Darien. I kept out of the way dodging from one place to another as it were.

I was molested and injured by being driven from place to place, and out of our own house[;] there were empty houses all along the coast. So was my husband in the same way.

Now, as I’ve pointed out before, there is a nasty irony when it comes to Southern Unionists. Sure, we can expect a reaction to Southern Unionists from those who were secessionists/Confederates, but should we expect the same from the Union soldiers? Some might not think so. But then, for anyone who looks into the story of SUs, the answer to that question becomes just about as obvious. What I find is that you take the Union soldiers when dealing with Confederate civilians, and simply water that down (to varying degrees) when dealing with Southern Unionists. Anyway… when it came to the day the Union soldiers came to town (Darien), the interaction with SUs reinforces this.

So, back to the story…

Charles Geary seems to provide the best descriptions of the day

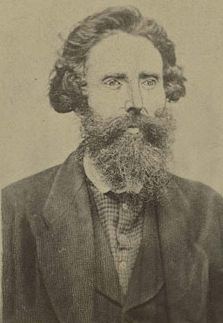

The real Col. James Montgomery, ca. 1858. On a sidenote, a year after this image was created, he hoped to rush to the assistance of John Brown, but was unable to do so because of snow in Pennsylvania.

I was present when her [his mother’s] property was taken and destroyed at Darien. It was taken and destroyed by the United States Soldiers, I knew them because they came up from where they had been blockading. They said they were U.S. Soldiers, I was captured by them and remained with them long enough to know that they were U.S. Soldiers. I became acquainted with the commander of those troops. His name was Col. Montgomery of the 2nd South Carolina, otherwords called 34th US Infantry Regt. By saying captured I mean they met me, and I went away with them voluntarily, on a proposition made to me by Col. Montgomery.

The regiment was systematically divided, portions were appointed to remove furniture etc from the houses, and other squads of soldiers came behind them setting fire to the buildings as soon as the other squads had cleared them of their contents.

There were five or six civilians present at the time of the taking besides the soldiers, myself, Alfred Noble, William Carter, Samson Walker, Mary Noble, Sarah Carter, and some others.

I saw them [the soldiers] destroy the property. The soldiers under the regular command of officers divided into companies, and under command of Col. Montgomery took buckets of tar and “light-wood” or pine knots and set fire to the buildings.

The Col. said he had to destroy all property alike whether white folks or colored peoples’ but he thought the Loyal people would all get paid for their losses by Government after the war.

I spoke to Col. Montgomery about the destruction of mother’s property he informed me he thought the loyal people would be paid.

My mother’s buildings were not singled out particularly. About three buildings in each block were set fire by these soldiers and thus the whole city was consumed. There were but three houses left standing in the city & they were on the outskirts. It was in this way my mother’s property was also destroyed.

As opposed to the portrayal of the 2nd S.C. (Colored) in Glory, Charles Geary seems to have remembered a much more orderly 2nd South Carolina, as it went to work in the village of Darien. Furthermore, from the way Montgomery is described in other sources, I don’t see him saying the words that were put in the actor’s mouth, for this particular scene… “I mean their little children, for God sake; they’re little monkey children, and you gotta know how to control them”. Additionally, the Glory Montgomery may have also been a bit more zealous in labeling the Darien’s citizens; “That man is secesh, and secesh is all the same, son.” The real Montgomery ordered even Unionists (including the free black Geary family) homes under the torch, but promised (a shallow promise?) compensation for their loss. Image from Glory.

I found it particularly interesting to see that Charles Geary even remembered that there was another regiment present… “the 54th Mass”, and a battery from Rhode Island.

I’d love to spend more time writing about how poorly (it seems) Col. Montgomery was portrayed in the movie, but that’s beyond the scope of this post. For those who are curious, a quick search on the Web should reveal enough (and, for those who wish, the Wikipedia entry offers a quick sketch). Back to the description of the burning of Darien…

Elizabeth Geary had additional things to say about the event:

The union army was not encamped in that vicinity when the property was taken and destroyed the land forces were on St. Simon’s island about twelve miles off. I do not know what branch of the army was there. The boats that burned the town were the “John Adams”, “Harriet Weed” & “Paul Jones” I think there was another but don’t know the name. They came up to the town about ten or eleven o’clock in the fore noon.

I saw the property burning from where I was back in the woods.

The federal troops burnt the whole town at the same time. The cow was driven to the federal camp and killed so I was informed. The rice and other stores charged for in bill was burnt up with the House they were all in the store room at the time of burning and don’t know whether the federal took any of the stores, or not before burning. I cannot say whether all my furniture was burned or not. I am sure that I saw a table that belonged to me it had been taken to South Carolina by the federal troops and sold so the lady said who had it that it is the only piece of furniture I ever saw that was in my house. I had Bacon and corn in my house when it was burnt. Don’t know what was taken out of the house.

The town was burnt and our property was burnt

… by three or four o’clock in the afternoon their work was done and they left. The city was in ashes.

Charles Geary appears to have been right in the midst of it all, and gave a much more thorough description on how things were taken,

I saw portions of the furniture from my mothers house taken out and carried onboard the boat I went on. I saw our cow taken from before the door, and put aboard the same boat. This cow I afterwards saw killed for beef on St. Simon’s Island. I saw portions of my mother’s furniture in use in the quarters of the Col & Lieut. Col. on St. Simon’s Island. There was no fighting that day of the burning in the city of Darien between the Federal and Confederate soldiers there had been no fighting previous, there never was any fighting at all there. The boat had thrown shells into the city and by this means one building was set on fire when the boat was approaching the city. That building was the property of a family named Reese, it was situated in the lower part of the city. No other building took fire from it it was a larger lot by itself. It was all of a quarter of a mile from my mothers house

After that day in Darien, Charles Geary became a cabin boy on the gunboat John Adams, and later, after falling ill with small pox, became a sutler in the Union army.

Charles’ brother, William, returned to Darien two days after the burning, and, of his parents’ furnishings, remembered,

I… saw that everything was gone or destroyed, and I know the property was all there before the Union forces went there to take and burn. I saw a part of the property at Beaufort SC at the Headquarters. I saw some of the furniture and a carpet that I could identify, also a chest if took which belonged to my father who was a carpenter. His name was on the chest. There was a set of Mahogany chairs cushioned hair cloth bottoms. There were two marble top tables and a sideboard I saw all these things in Beaufort SC … they were held as confiscated property and I saw them sold by Government sale.

William Andrew Geary served soon after on the Wamsutta*, and later received a discharge.

In almost a month, Elizabeth and her husband sought help in fleeing the area, after local Confederates had sent warning that the family should leave, after having been suspected of giving Union forces information (which they had).

I did leave the so called Confederate States… and so did my husband and family. I left the fifth or sixth of July in 1863. We went first to Beaufort. We sent a private message to “Capt. Kitridge”** of the blockader “Waumasutta” [sic] and he came up and took me aboard in a small boat. The Rebels found we were in communication with the Yankees and ordered us to leave; they gave us four hours to get away. We heard previously that the order was coming to us to leave, and we sent to the steamer the night before we got the order. And before we got the order to leave we received a signal from the steamer that they would come for us. The signal was this: the steamer left her anchorage early the morning after we sent to her, and ran up a little way towards us then returned. We knew from this signal that she was to come up after us that night. They came up that night and we got on board a little after four o’clock next morning, she had got a aground, and was delayed some; when we got on board, my husband directed the captain to where the Rebel camp was, & the captain shelled them from the steamer.

On my way to Beaufort on the Mr. “Oleander” Capt. Bennett, I made great numbers of small signal flags, hundreds of them; I worked on them all the time.

I remained at Beaufort within the Union lines until the close of the war. I was engaged in baking bread, cake, & pies, for my living.

I never did any thing for the U.S. government or its army or for the union cause during the war except what I have already stated in … while in Beaufort taking care of the sick. I was close by the hospital there. I was not alone in this work; there was a good many lady teachers from the North & all the white folks helped.

Elizabeth recalled that she was given no voucher for the property taken. She and her husband complained to the officers at Hilton Head, and even to “Genl. Gilmore who was in command”, but Gilmore “said he could do nothing as that present time but would be paid by the government. He gave us about a months rations.”

In the early 1870s, when Elizabeth finally filed her claim, she asked for compensation in the amount of $3,400, which included $300 for the kitchen furniture and crockery; $50 for the “good milk cow; $50 for the grocery store, $500 for the house furniture; and $2,500 for the dwelling house and outbuildings.

After hearing all the testimony, and reviewing the claim, the Special Commissioner remarked,

The claimant in this case is one of the most accomplished intelligent lady-like colored woman I have met with in the south any where. Her sons too are men whose character stand above reproach industrious and applying themselves.”

She and her family had adequately proved loyalty to the Union. Yet, in the end, compensation fell well below the mark. The Claims Commission awarded Elizabeth a mere $30.

*Thanks to Andy Hall for assistance in figuring out that the Waumasutta (as remembered by Elizabeth) was actually the Wamsutta, “a 270-ton screw steamer built at Hoboken in 1853 and taken into the Navy in September 1861. She was sold and re-documented as a civilian steamer on July 26, 1865. It appears her engines were removed and she was converted to a barge, being removed from the registry as a steamship on July 5, 1879.” Andy’s source: C. Bradford Mitchell, ed. Merchant Steam Vessels of the United States, 1790–1868 (The Lytle-Holdcamper List). Staten Island, New York: Steamship Historical Society of America, 1975, 225.

**Also of interest was “Capt. Kitridge” [sic], who, Andy remembered, was the “Terror of the Texas Coast”. See this link for more information about Kittridge.

Harry Smeltzer

January 18, 2013

Robert, before I started blogging for myself, I made two posts on the Burning of Darien during a guest stint at Civil War Bookshelf. Check them out here: http://cwbn.blogspot.com/search?q=darien

Robert Moore

January 19, 2013

After having just read the two pieces, I’m even more curious about Montgomery. The more I read about him, sounds like he was just Harpers Ferry-short of John Brown!

Bummer

January 19, 2013

Another great read. Thanks for the research and and commentary. This student learns something new every time you post.

Bummer

Robert Moore

January 19, 2013

Thanks, Bummer!

Craig Swain

January 19, 2013

The local historical marker in Darian (http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?MarkerID=47426 ) offers the bare facts. When I lived down that way, I frequented the town. Always thought a kiosk type interpretive exhibit would be proper – offering views from different perspectives. But alas, I’m just a poor old marker hunter.

As long as we are talking markers, Montgomery was linked in local oral tradition to the “23 old men” incident recorded on a historical marker north of Darien: http://www.hmdb.org/marker.asp?marker=10508

But…. it was the Navy, not the Army that captured those men.

Robert Moore

January 20, 2013

Now I’m curious to see, if by chance… any of the 23 happened to apply for a claim.

Craig Swain

January 20, 2013

The Navy ORs have a complete list of those captured (and IIRC the number was 25 or 28 and not 23). There was much dialog at the time between Dahlgren and the CS commanders about exchanges. At first Dahlgren wanted to exchange them for officers captured in the failed raid on Fort Sumter. Eventually, the Navy just released any of the captives that had no direct connection with the war effort.

Jefferson Moon

January 20, 2013

Why was the town burned ???

Robert Moore

January 20, 2013

There was no strategic importance to it. Harry’ s links point out also that the action came about at local command level. Of course, Shaw condemned the act, and I think one of Harry’s posts gives Lincoln’s reaction.

John Rogers

January 25, 2013

Robert,

Thoroughly enjoyed this post and your excellent blog in general. Our family in Georgia has a similar story that I’ve written about at http://preservefamilyandfarm.wordpress.com/

John Rogers

Robert Moore

January 27, 2013

Thanks! Great post on your blog also!

Leslie Bauman Fisher

February 28, 2013

Very interesting post, Robert. I wonder what the justification for the $30 compensation was. What do you think happened to the family?

Robert Moore

February 28, 2013

Thanks, Leslie. I didn’t follow the family after the date of award (March, 1875), but it appears they remained outside of Savannah, in Chatham County. One can only imagine the struggles they went through to recover from the tremendous losses. It would be great to connect with any descendants, to learn any oral stories passed down about the matter.

maggietoussaint

March 7, 2013

Robert, I’m a newspaper reporter in Darien, Ga. I’d love to connect with you about this story and to learn about your original sources so that I may also write a bit about it for our series to promote the upcoming reenactment of the Burning of Darien. Please shoot me an email so we can more easily communicate: maggietoussaint at darientel dot net. I look forward to hearing from you.

Robert Moore

March 7, 2013

Happy to help, Maggie. An email is on the way.