I thoroughly enjoy taking this…

… and coming up with this…

Name: Konoginsky, Gustave (or Gustav)

Unit: 41st New York Infantry, Company A

Circumstances of death: MWIA 6/8/62, Battle of Cross Keys

Date of Death: 6/12/62

Age: 19

Pensions received (widow/mother, etc.) based on his service: None (though 80 out of his company received pensions).

… and so, I created this…

More than names in stone: Union soldiers in Staunton National Cemetery

Yes, yet another “spoke” (aka “micro-blog”) in the “hub,” but it is a side project of mine that I have been working on, on and off, for a few years. It’s been “hanging-out” in the right hand sidebar for a while now, but I’ve moved it over to left along with the rest of my micro-blog feeds.

I didn’t start looking into the information about the soldiers in the national cemetery in Staunton to create a book or even a flimsy set of papers, stapled and tucked away in some file drawers in a library. I did it because I think that the Union soldiers buried in national cemeteries weren’t given a great deal of consideration in the way of identification after the war. So, I’d like to make the info accesible to others on the Web.

Ever since my trip to Andersonville nearly twelve years ago, this pattern of poor grave identifications really got to me. Maybe it’s because I’m a veteran myself. I hate unknown graves… kind of reminds me of leaving behind one’s own dead on the battlefield.

Short story… oh, heck, I’ve mentioned a little about this before, but… well, maybe you might want to grab a snack and something to drink… and then lean back and start reading… I’m feeling like I’d like to write this one out a bit. Let’s see if I can get through without embellishing too much… 🙂

In mid April 1997, not long after reporting to King’s Bay, Ga., I went to Andersonville to see the grave of a distant Moore cousin (actually a half 1st cousin, four times removed), James Draper Moore, Co. B, 1st Potomac Home Brigade Maryland Volunteer Cavalry (aka “Cole’s Cavalry”).

Piecing together the basic elements found in Moore’s service record and tying them to

them to  the different stories found in several works focused on Mosby and his men, I was able to pull together a bit to better understand what happened. Moore was captured on Loudoun Heights while on picket duty (apparently somewhere along the Hillsboro road, where Piney Run crosses… Craig, when you read this, if you are ever up that way again, I wonder if you can snap a photo… maybe, please?), along with five other members of the same company (Hamilton Wolf, George Weaver, Isaiah Nicewander, John Newcomber, and Walter Scott Myers), on January 10, 1864.

the different stories found in several works focused on Mosby and his men, I was able to pull together a bit to better understand what happened. Moore was captured on Loudoun Heights while on picket duty (apparently somewhere along the Hillsboro road, where Piney Run crosses… Craig, when you read this, if you are ever up that way again, I wonder if you can snap a photo… maybe, please?), along with five other members of the same company (Hamilton Wolf, George Weaver, Isaiah Nicewander, John Newcomber, and Walter Scott Myers), on January 10, 1864.

Having planned for a night attack (in freezing temperatures and snow, no less) on the camp of Cole’s Cavalry, Mosby, of course, wanted to keep the element of surprise and make certain that this picket was taken out in order to free a path for his escape. Long story made short here, Mosby didn’t do so hot, some may have even said he “got whooped.” By the time that Mosby had decided to withdraw, he had suffered severe losses, including the wounding of his younger brother “Willie.” In addition to the six captured Federal troopers, Cole’s battalion had lost six killed and fourteen wounded. However, the men lost from Mosby’s command were deemed by one ranger as “worth more than all Cole’s Battalion.” Considering all of this, a truce was made later that morning

Having planned for a night attack (in freezing temperatures and snow, no less) on the camp of Cole’s Cavalry, Mosby, of course, wanted to keep the element of surprise and make certain that this picket was taken out in order to free a path for his escape. Long story made short here, Mosby didn’t do so hot, some may have even said he “got whooped.” By the time that Mosby had decided to withdraw, he had suffered severe losses, including the wounding of his younger brother “Willie.” In addition to the six captured Federal troopers, Cole’s battalion had lost six killed and fourteen wounded. However, the men lost from Mosby’s command were deemed by one ranger as “worth more than all Cole’s Battalion.” Considering all of this, a truce was made later that morning and Captain William Henry Chapman (now when I learned this, it really made the hairs stand up on the back because Chapman was a central focus of my first book, so I’m extremely familiar with the man and his life… not to mention that, like me, he was a native of Page County) dispatched a messenger into the Federal camp with an offer for an exchange. For the recovery of his men, Mosby would return the six captured Federal troopers. Cole refused to receive the offer, ultimately sealing Moore’s fate (and that of most of his fellow pickets).

and Captain William Henry Chapman (now when I learned this, it really made the hairs stand up on the back because Chapman was a central focus of my first book, so I’m extremely familiar with the man and his life… not to mention that, like me, he was a native of Page County) dispatched a messenger into the Federal camp with an offer for an exchange. For the recovery of his men, Mosby would return the six captured Federal troopers. Cole refused to receive the offer, ultimately sealing Moore’s fate (and that of most of his fellow pickets).

Moore and his pards were first sent to Belle Island, Richmond, Va. (ever been there? I went in late winter 2007 and found the place extremely depressing and poorly maintained). Later, they were taken off the island, loaded into train cars and sent to Camp Sumter (aka Andersonville). On August 30, 1864 (only seven days after what was considered the worst day in Andersonville’s history for deaths), when the prison camp was at its peak for disease and deaths due to overcrowding, James D. Moore died of scobitis (scurvy). His grave is #7273.

So, back to the present… well, at least to 1997 when I made the trip…

After making what I found to be an incredibly long drive from southeast Georgia, I entered the park, secured information that would help me make my way to the headstone, and found it. However, what I found threw me for a loop. The name and unit information were all wrong (If I remember correctly, I think the old headstone identified him as “M.L. Moore” from Maine, someone, incidentally, who actually died in Salisbury Prison, in North Carolina… or at least that is what I think I remember one of the park rangers later telling me). It took me a year to get the whole matter straightened out, but he finally got a new headstone before I closed-out my last tour in the Navy. I never got to see the new headstone in person, but I was able to secure photos courtesy of a friend who made a trip through Andersonville a few years ago.

I was thrilled that I was able to do something like this. Yeah, I know, the new stone isn’t exactly right either (“Potomac Home Guard” instead of “Potomac Home Brigade”), but it’s a significant improvement. It also made me think about how many other soldiers who might be identified incorrectly.

Oh, by the way, before that previously mentioned friend headed down to Andersonville, I asked him to snap photos of the headstones of the other men captured along with Moore.

Walter Scott Myers’ headstone misidentifies him as L.S. Myers and provides no unit information. He died on May 23, 1864 of chronic diarrhea and rests in grave #1307. His mother applied for and received a pension.

Weaver’s headstone is accurate, but does not identify unit. He died on September 21, 1864 of diarrhea. His remains rest in grave #9409. I haven’t figured it out yet, but it looks like there may have been some pension acvitity after his death. I need to see if he had a wife who applied or his mother applied.

Wolf’s headstone is like that of Weaver… again, no unit information. Wolf died on November 24, 1864 and rest in grave #12147. His mother later applied for and received a pension.

I can’t find my photo of Newcomer’s headstone right now, but his headstone misidentifies him as “John Macomber” and, like the others, there is only the identification as a soldier from Maryland, but no unit info. He died August 6, 1864 of diarrhea and rests in grave #4881. It looks like nobody applied for a pension based on his service.

Out of all who were captured that cold night in January 1864, only Nicewander survived Andersonville. Born ca. 1842, he was from Welsh Run, Montgomery, Franklin Co., Pa., a son of Hannah Nicewander. He died sometime before October 1886, and I wonder if it was from the effects of POW camp. His mother applied for a pension based on his service, but did not receive one.

I also found pension records for James D. Moore’s parents. James’ mother’s application was dated 7/26/1880 and his father’s was dated 5/23/1888. Moore’s father was Hamilton Alexander Moore (1812-1891), a half-brother to my third great grandfather, Cyrus Saunders Moore (1829-1904). J.D. Moore’s mother was Christiana Fink Moore (1816-1888). Both Hamilton and Christiana, as well as many other Moore family members, are buried in St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church Cemetery, Clear Spring, Maryland… over 750 miles from the grave of their son at Andersonville.

So, there you have it… the full story of why I like to identify the misidentified Union dead, and how it carries over to the Staunton National Cemetery project. Like the title of the micro-blog indicates… there’s more to it than names in stone.

* You can also find James Draper Moore in Find-a-Grave. I placed his info and a photo of his headstone there, along with that of his parents. Follow the links to the parents near the bottom of this page.

caswain01

December 31, 2008

Robert, Let me look through the archives and see if I have something of that vicinity on file. (Ok it is not really the archives, but I wanted to make my photo library sound important!)

Craig.

Michael Sorenson

January 23, 2010

Hello, Robert,

I am researching William H. Chapman, who I believe fought as a ranger with Mosby during the Civil War. I believe that Chapman was the man who shot and killed the real subject of my research, J. Sewall Reed of the Cal Hundred who was killed during a fight with Mosby near Dranesville, Virginia.

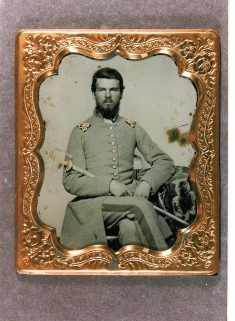

I note from your blog that you have written about Chapman. On that blog appears a tintype of a Confederate officer who I presume to be Chapman. Do you know where I might receive a copy of that scan?

Thanks for your help!

Mike Sorenson

MSoren500@aol.com

Robert Moore

January 24, 2010

Hi Mike,

Yes, indeed… Chapman was not only with Mosby but was also his second in command. Also, yes, Chapman killed Reed in the fight at Anker’s shop. In the heat of the fight, Reed indicated that he was surrendering… this while von Massow was bearing down on him by horse. Seeing that Reed was offering surrender, von Massow passed by Reed (he was at such a speed that he could not take Reed as a prisoner). As von Massow passed him, Reed turned and fired his pistol at von Massow. Having witnessed his friend’s fall (von Massow was severely wounded, but survived), Chapman rode up and fired at Reed, the bullet finding it’s mark. Reed fell near von Massow, and attempted to return fire, but slumped over dead.

I was granted permission to use the photo of Chapman by one of his granddaughters (who also sent me a copy of the image). She passed several years ago. It is likely an image of him while he was with the Dixie Artillery, not while he served with Mosby.

Don Severn

August 18, 2010

I’m just getting into the geneology bug and have traced my Great-great-great-uncle (Hamilton Wolf) to your entry. This was my G-G-G-grandfather’s brother on my mother’s side of the family. They family name is Wolfe and Hamilton’s parents had the “e” at the end of their name. Wonder why the “e” was dropped for poor Hamilton? Anyway, seeing the headstone is wonderful. Thanks for taking the time to shoot the pic.

Cheers,

Don

Gary Smith

June 24, 2011

Walter Scott Myers was the son of my great great grandparents Emanuel & Tamzin Myers. He was born around 1842 in Clear Spring, Maryland. His Father, Emanuel, was also in Cole’s Cavalry, enlisting shortly after Walter Scott Myers was captured at Loudoun Heights on January 10, 1864. It is my educated guess that maybe he enlisted in order to find out where Walter Scott was and try to find him alive. Emanuel survived the war but I lost track of him afterwards. Both of Walter Scott’s parents were born in the Clear Spring, Maryland, area in or around 1815. Tamzin, his Mother, died in 1898 and is buried at St. Paul’s Lutheran Church at St. Paul’s, Maryland, a few miles east of Clear Spring on route #40. I can not account for Emanuel, his Father, after his discharge in 1865. If anyone has any information on Walter Scott, Tamzin, or Emanuel Myers, I would like to hear from them. I can be contacted at gsmith5720@comcast.net. I hope this information is helpful to anyone interested in the Myers family of Western Maryland.

Gary Smith

March 9, 2013

This mentioned Emanuel Myers was not the father of Walter Scott Myers, whose father, Emanuel, died Oct. 10, 1855. I was in error.

Gary Smith

October 23, 2014

Walter Scott Myers’, born in 1842, parents were Emanuel & Tamzin Myers. Walter Scott Myers’ grandparents were Susanna Barkman & Lewis Myers. They did not have a son, Walter Scott Myers.

Susann Clendening

April 21, 2024

Doing genealogy on my family came across Amanda Elizabeth Moore who married a 5th cousin, Charles Henry Smith, 1899 Maryland. Amanda’s parents were John Henry Moore (1844-1927) and Martha Susan Myers (1845-1904). That set off a deep dive because I have Myers in my paternal line (always looking for another connection). Martha Susan’s parents are Emanuel Myers and Tamzin Myers, yes both surnames are Myers. According to the 1880 Census, Tamzin’s parents are from Pennsylvania. Found a set of grandparents in your blog, but not sure who they belong with. Had family on both sides in the Civil war, Walter Scott Myers would have been mine along with quite a few of Mosby’s Rangers. Thanks for the help and what you are doing. I too have been to Andersonville.